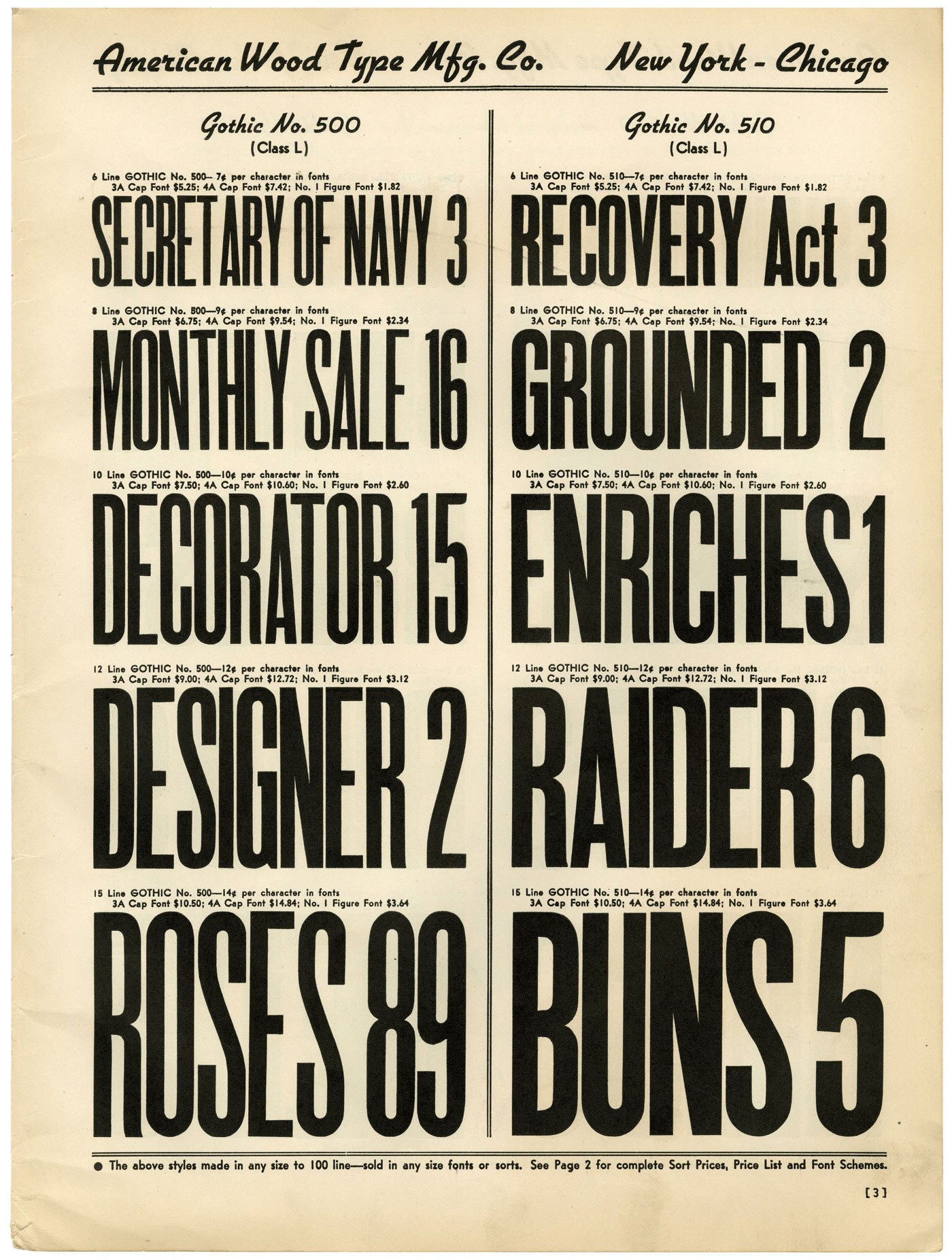

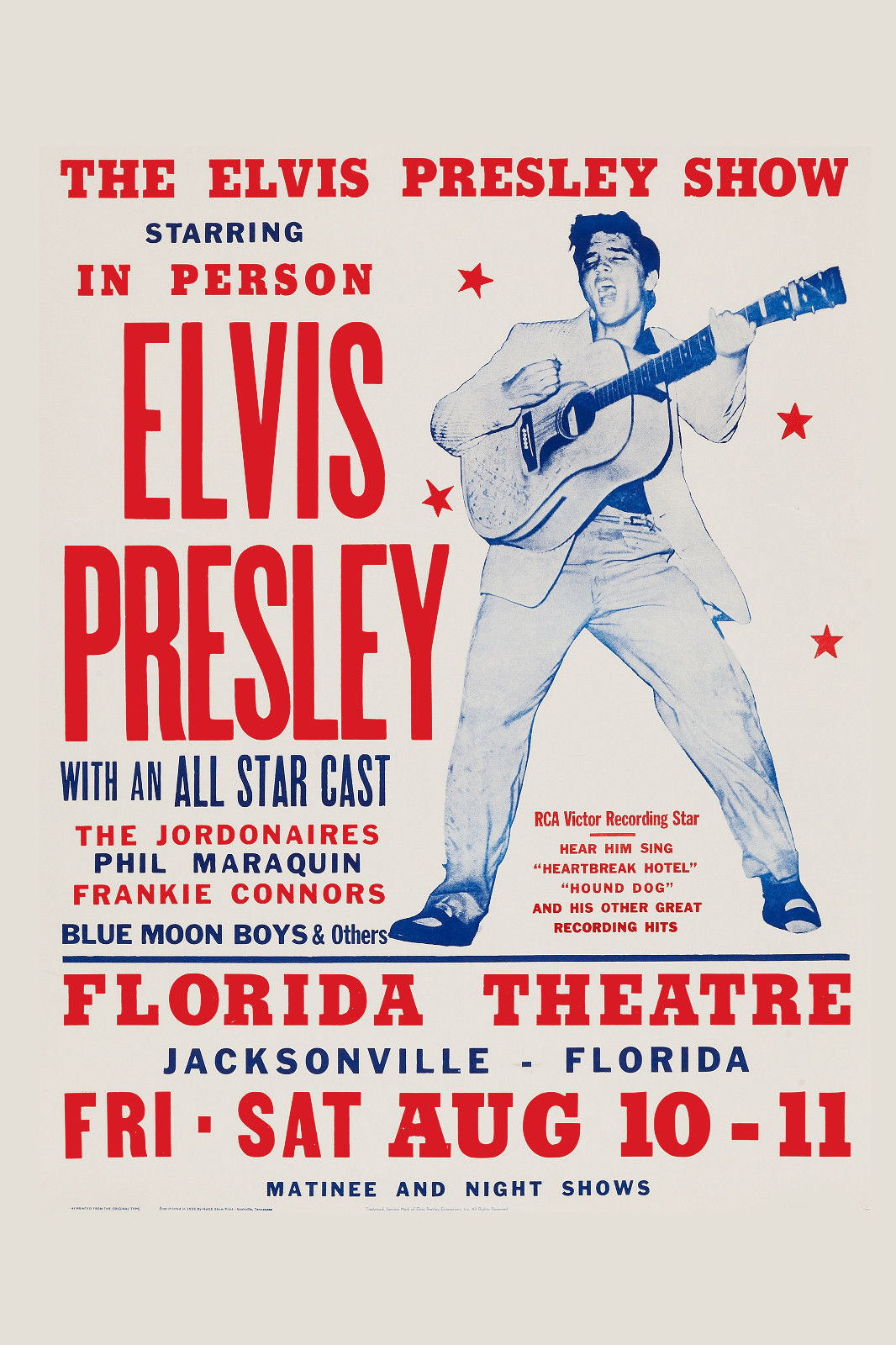

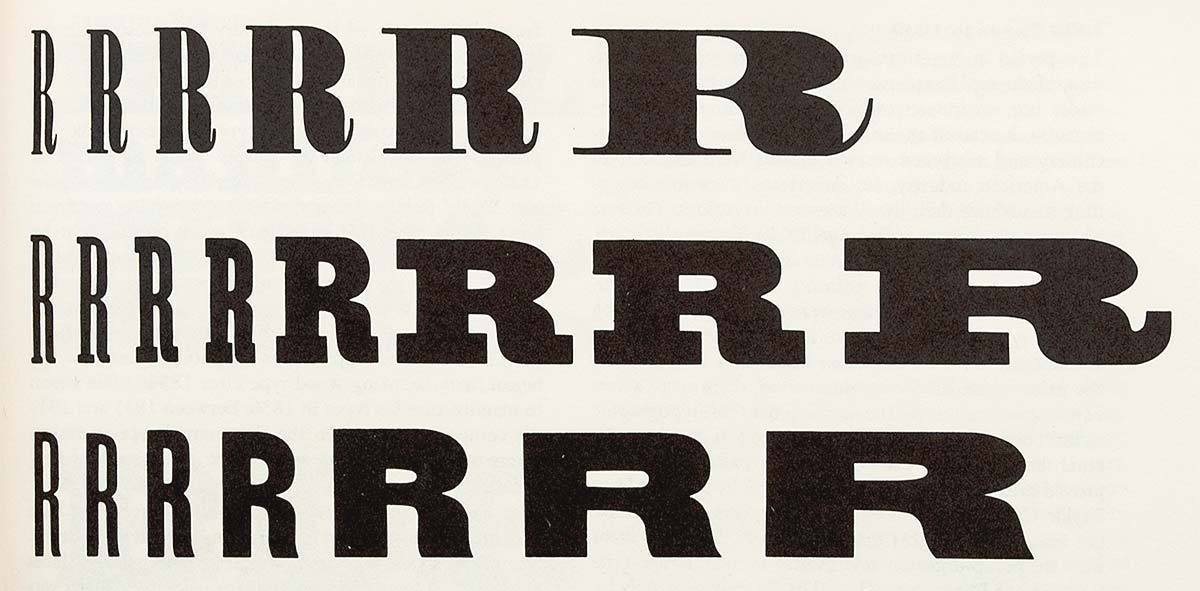

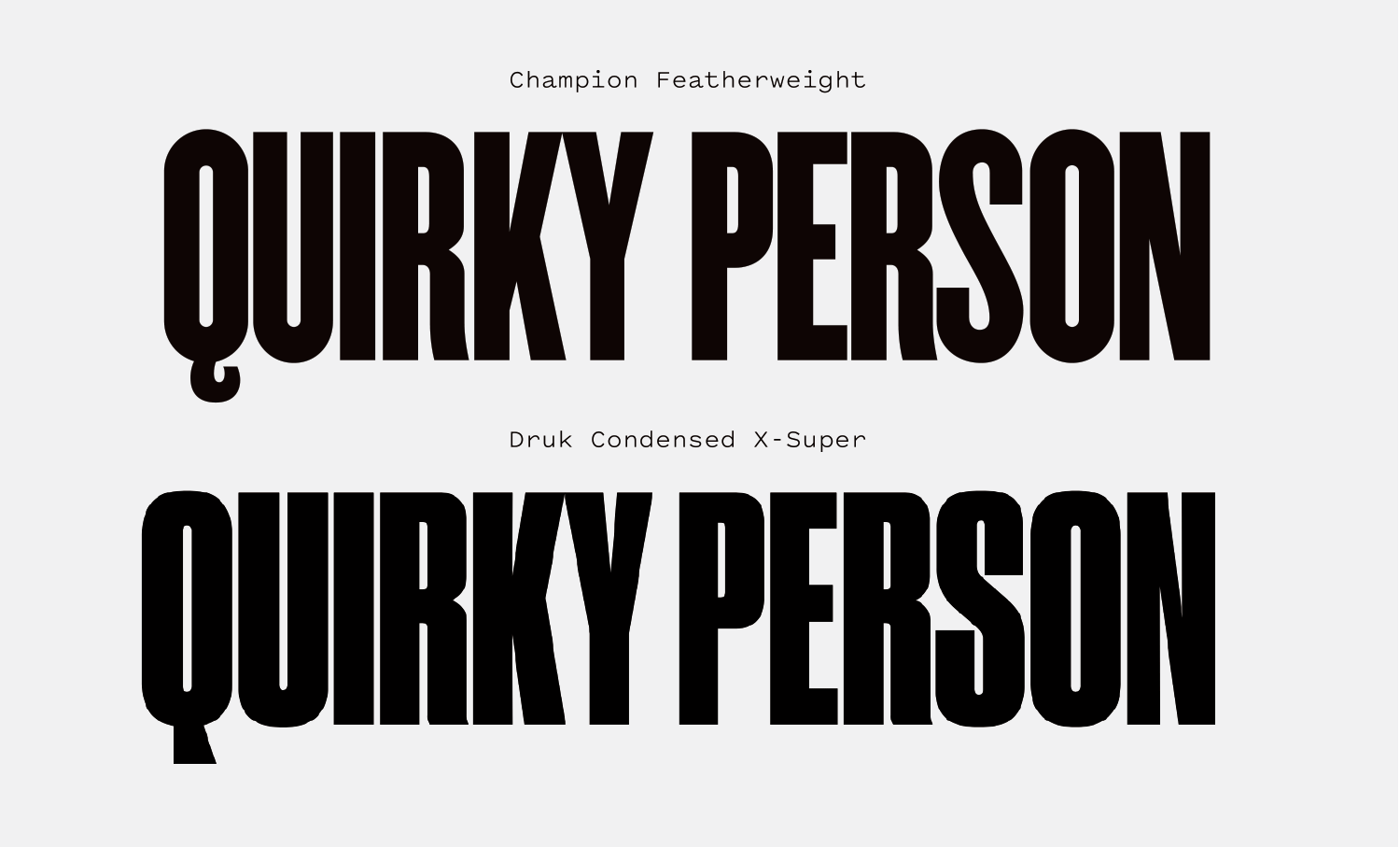

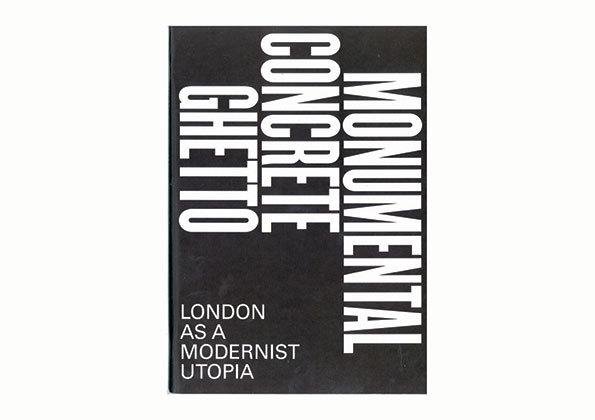

Champion Gothic is a love letter to wood type, and the early attempts type cutters made at interpolating a single style into a variety of widths. Wood type in the US was pioneered by mad scientists who strained good taste and legibility in an attempt to cover the broadest range of ornament, width and weight, and Champion carries that heart and passion through in its design.

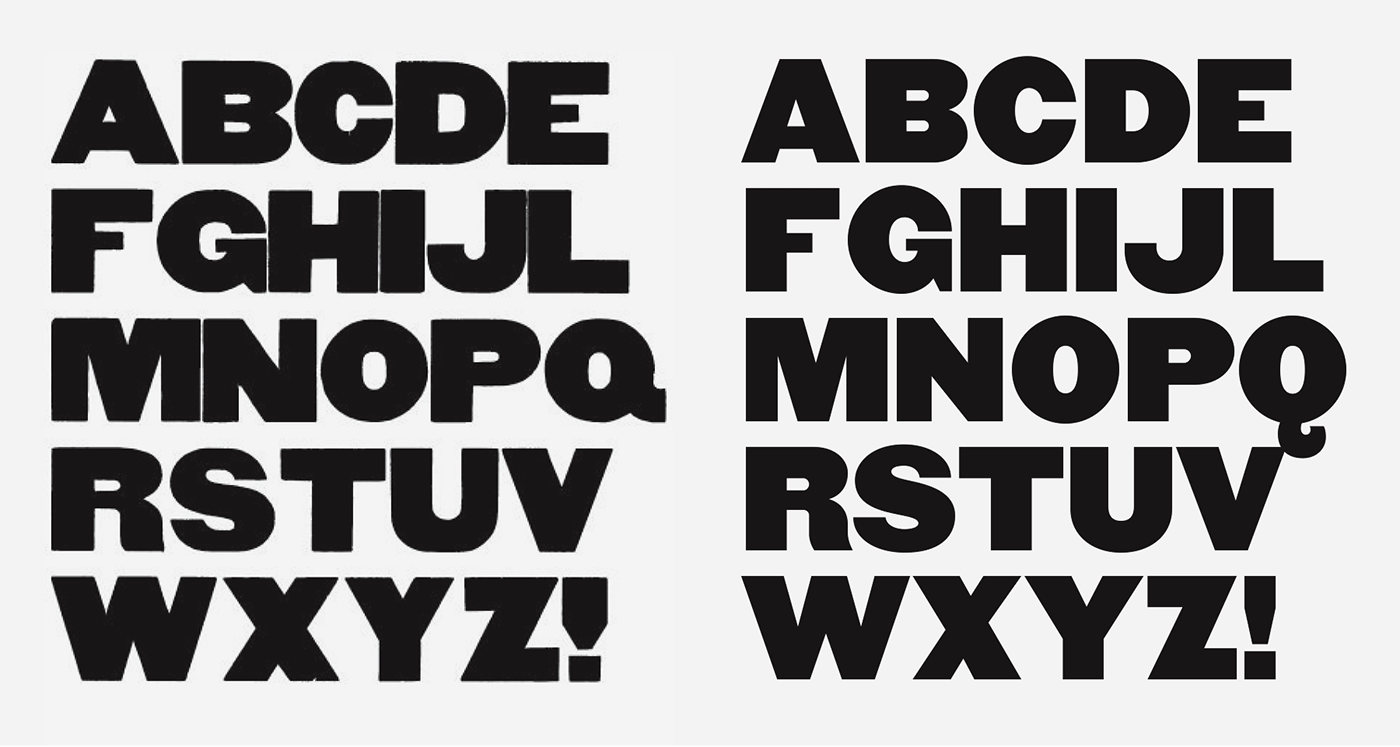

There are a lot of digital revivals of wood typefaces available, but I don’t think any of them combine the warmth of the original designs with the craft Hoefler brings to Champion. Many of Champion’s weights are close translations of classic wood typefaces, lending the family a slightly mismatched, eclectic quality. There are several details that carry through regardless of the weight: the incised spur on the “G”, the curved leg on the “R” and the luxurious curve on the flag of the “5.” These shared details lend the family just enough consistency while letting each weight stand confidently as its own design.

While the more interpolation-heavy design of its successor, Knockout, begets more weights, widths and overall consistency, each weight of Champion feels like its own person, optimized only for itself and no one else. There are no “forced” or awkward weights in Champion because none of them are particularly obliged to obey the rules set by each other. It’s just a bit awkward and mismatched in a way that suits the fast-paced, slap-dash nature of the job printing typefaces it emulates.